Water in the mountains

Water: a bridge between Earth, glaciers and sky

Before flowing through domestic taps, water makes a long journey that often starts at hight altitudes, sometimes right from a mountain glacier.

And the story of glaciers starts in the sky, when snow falls and lands at high altitudes or latitudes.

Glaciers are the end-product of a slow transformation of snow. Snowflakes are transformed into grains, then compacted, the air trapped in the snow then being expelled.

A process of metamorphosis turns fresh snow (with a density of 50-200 kg/m3) into old snow (400-830 kg/m3) and then into ice (at times over 900 kg/m3).

Depending on their shape, size and the region in which they are found, glaciers can be of the mountain or continental type.

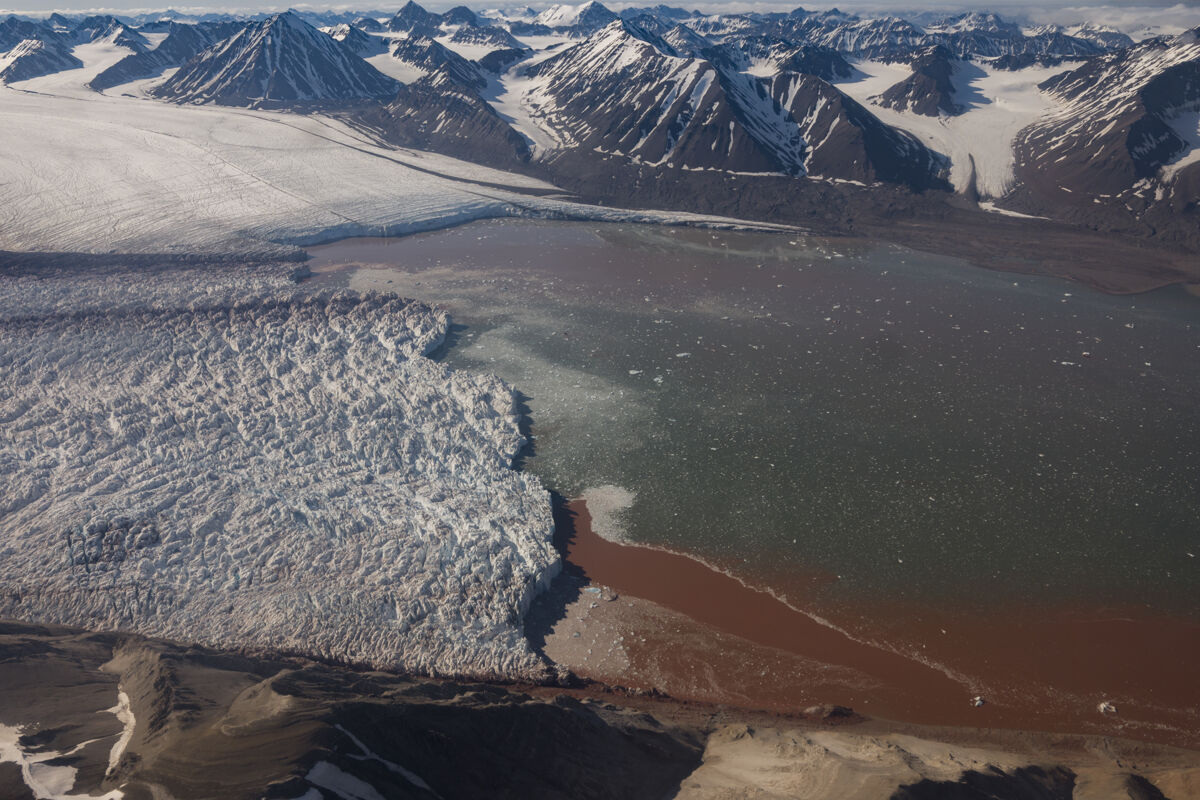

Greenland

Delphotostock | Rights reserved | Adobe StockContinental glaciers, also known as ice sheets, often cover vast areas and are typically found in polar regions such as in Greenland and the Antarctica.

Kilimanjaro

Lubo Ivanko | Rights reserved | Adobe StockMountain glaciers, including Alpine glaciers, are smaller in area and are found at increasingly high altitudes as the latitude decreases.

In the Svalbard Archipelago, about 80° north latitude, mountain glaciers extend down to sea level, while the glacier on Kilimanjaro, almost at the Equator, is situated well above 5000 metres and is fast disappearing due to global warming

A mountain glacier is formed when the ice mass, due to its weight, starts to deform and slide downhill, creating the ice tongue that is channelled down a valley.

As it reaches lower altitudes, the ice mass meets higher temperatures until it starts melting.

This slow flowing river of ice therefore starts with the accumulation of snow at altitude and ends at the foot of glacier, lower down, where meltwater forms a glacial stream.

With rising temperatures, melting is outpacing the accumulation of new ice mass, and the descending body of ice is melting at higher and higher altitudes. The glacier thus loses volume and appears to shrink.

In past times, however, such as during the Little Ice Age between 1600 and 1800, accumulation outpaced melting and glaciers advanced downhill, pushing before their terminal moraines: accumulations of rocky debris were subsequently left there when the glaciers once again retreated.

Advancing and retreating glaciers

Glaciers form by steady accumulation of snow. For a glacier to grow, snow from winter falls cannot completely melt away during the following summer. If however the temperatures are too high, as in recent years, melting exceeds such winter accumulation, causing the glacier to retreat until it disappears.

The growth and retreat of ice-sheets and glaciers is a normal consequence of natural climate variability. In the past, however, such changes came about very slowly compared to what we see today.

There is life in icy places

At first sight, glaciers can appear to be just masses of lifeless frozen water. But if we look closer, we see that glaciers too are inhabited by a range of organisms. Some live on the surface, others at the base, while yet others even survive inside the ice mass itself.

Diamesa steinboecki

Special micro-environments can form on the surface of the glacier capable of hosting very specific animals and plants. The most common and species-rich communities are dominated by bacteria, single-celled organisms and even insects.

Boreus hyemalis

The Boreus hyemalis, a small insect also known as the ‘snow flea’, which moves by crawling or jumping over the snow, is typically found around the ice-snowline.

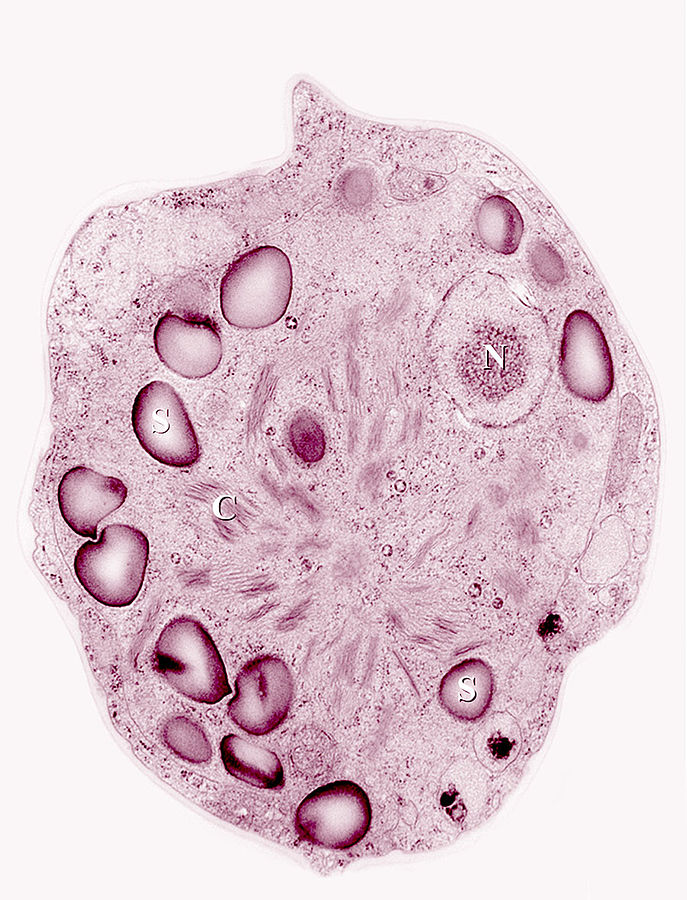

Chlamydomonas nivalis

An example of a microorganism is the small snow alga Chlamydomonas nivalis found on several glaciers in the Alpine chain, which causes the snow to turn pink wherever it is present.

However, since such algae darken glaciers, they speed up melting. This phenomenon has been studied in the Arctic and Antarctic and might well intensify in the future due to climate change.

Apart from insects and snow algae, other types of algae are also present on glaciers that can survive on the ice surface during the months when summer melting takes place.

Such glacial algae are also hastening the melting of ice in south-western Greenland. It has been noted how their presence is changing the visual properties of the ice in the Swiss Alps, in terms of how it reflects the sun’s rays.

Everything on this planet is linked: carbon dioxide, rising temperatures, algal growth and the melting of ice.

This is a living planet featuring an inextricable and wonderful network of relationships and connections. If it is disturbed, there is no way of knowing how the system as a whole will react.

The downhill journey of glacier water

In past centuries, the ru, derived from the Latin rivus, was a traditional method used to collect glacial meltwater. Typical of the Val d’Aosta, the ru is an old system for carrying glacial meltwater that could be integrated into the natural landscape without causing negative impacts on the mountain ecosystems.

The rus are irrigation canals built to allow crops to be grown on the arid mountain sides exposed to the sun. Most of them were built between the 13th and 16th centuries.

Their purpose was to collect water from glacial streams and distribute it to farmland, mountain pastures and the hilly areas on the valley floor via complex sub-networks.

Some rus were real engineering masterpieces. One example is the Ru Courtaud, which collected water from the glaciers in the Val d’Ayas and channelled them along a network stretching 25 kilometres.

Retreating glaciers and earlier melting of snow are currently causing water supply problems for ecosystems and many mountain communities in need of water conservation strategies.

In Ladakh, in north-western India, ‘ice stupas’ are built to store frozen water during the cold, dry winter months for release in the spring.

In Gran Paradiso National Park, a joint project with the Ministry of Environment and Energy Security provides for natural irrigation of some high-altitude grassland areas using an updated version of traditional forms of mountain irrigation.

Alpine lakes and deep water

Aerial view of the melting Rhone glacier and the glacial lake in the Swiss Alps

Nick Fox | Rights reserved | Adobe StockWhen not collected and channelled by human intervention, glacial meltwater tends naturally to flow downhill to form lakes and watercourses.

The Alpine lakes are major reminders of the glaciers that were present in these areas during the Quaternary period. Indeed most Alpine lakes are of glacial origin, having been shaped by the erosive force caused by the movement of ancient glaciers and the sediments they carried with them.

There are different types of glacial lakes. From cirque lakes to moraine-dammed lakes, from lakes at the head, side or foot of a valley to glacier-blocked lakes.

Alpine lakes are not eternal. Their longevity depends on their shape and depth, as well as on the quantity and intensity of the flows feeding them.

Water carry various kinds of suspended sediments that gradually fills the basin of the lake, making it shallower and sometimes forming a peat bog.

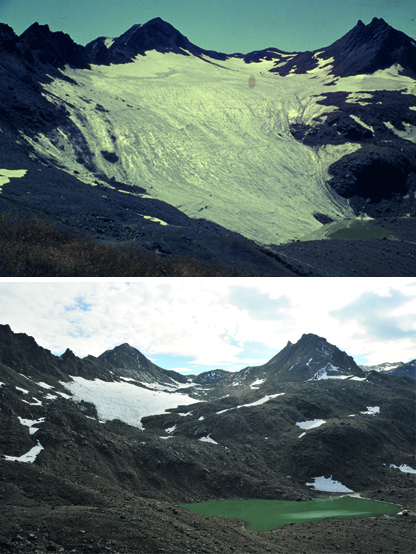

Ban glacier, 2021

Gabriele Tartari | Rights reservedProglacial lakes are especially interesting and are formed near the front of a glacier by a natural damming action, caused by a moraine or by ice as the glacier retreats.

The proglacial lake formed by the Ban glacier in Piedmont is one example of this. The effects of climate change can clearly be seen here.

The rapid retreat of the Ban glacier and the formation of the lake have been amply documented by the National Research Council’s Water Research Institute (CNR IRSA) by means of a series of images starting in the 1960s and continuing into the present.

Ban Glacier 1964 (top) and 2009 (bottom)

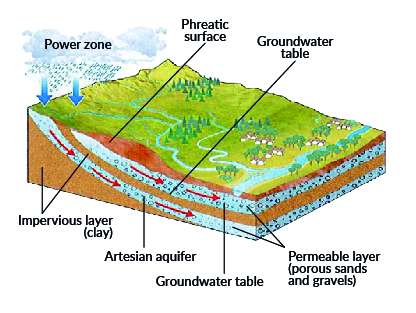

Groundwater must be added to the glaciers and surface water: rain and snow meltwater not only flow overground or feed the lakes, they also drain into the ground and sink until they meet a layer of impermeable rock.

This forms an area of water-bearing fractured rock or sediment known as an aquifer. Aquifers are sometimes in contact with water rising from areas deeper in the Earth’s crust.

Groundwater forms an important reservoir that is invisible from the surface, the size of which depends on the properties of the soil and rock.

The diagram shows a vast area with mountains from which the rivers descend to the valley, and the subsoil section, where there are aquifers, a more superficial one, the phreatic aquifer, and a deeper one, the artesian aquifer. Both types of aquifer are fed by precipitation water and of melting glaciers, which permeates the subsoil and forms them when it finds an impermeable layer. The drawing shows how the deep aquifer is isolated from the surface system because it flows between two layers of impermeable soil, while the phreatic can also come into contact with the waters of rivers on the surface.

Aquifers provide human beings with most of their water for drinking and farming purposes and so their protection is becoming increasingly important. The quantity and quality of groundwater is under threat both from increasing drought and from pollutants released on the surface and filtering into the earth.

Groundwater often flows from its subterranean level out into the valleys, thus enriching the hydrological system of the plains and feeding springs (often adapted by human intervention as fountains or used for irrigation) and the deep aquifer system, on which many aqueducts draw.

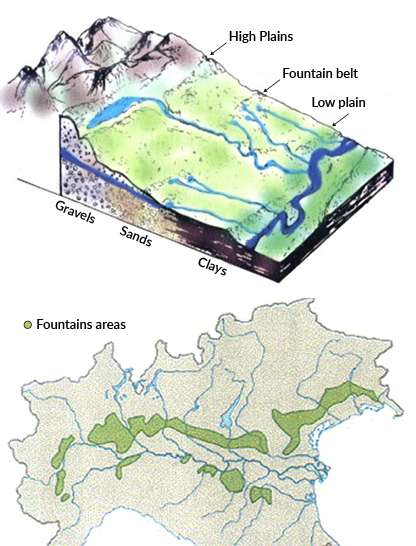

The illustration represents the surface water system of the mountain lakes and rivers that descend from high altitudes to the lower Po valley, and the aquifers present in the subsoil that cross three different types of soil with ever finer granulometry as one approaches the low plain, going from gravel to sand to clay. Between the high and low plains there is the strip of fountains characterized by the presence of springs. The band of springs is mostly distributed in the areas immediately above the Po and immediately above the Veneto coast.

In this last case, wells can sometimes bring to the surface water that fell as rain thousands of years ago. The deep aquifers are valuable because they have not been contaminated by human pollution of the environment.

Flowing water

River Isorno, Valle Isorno

Angela Boggero | Rights reservedWater from glacial meltwater and high-altitude springs that does not filter into the ground flows into mountain rapids and eventually into the quieter streams of the valley floor. Surface and groundwater often accompany each other downhill, sometimes mixing and sometimes following separate paths.

River Isorno, Valle Isorno.

Angela Boggero | Rights reservedAlong the way, the water’s properties are gradually but profoundly altered by substances washed off the rocks.

Rio Valgrande area

Angela Boggero | Rights reservedIn the case of surface watercourses, the flow rate, gradient, type of substrate and bank vegetation.

Stelvio National Park

Gianfranco Varini | Rights reservedJust like glaciers, watercourses have their own rhythms. In streams fed by glaciers, the flow rate depends on the speed at which the ice melts and therefore changes throughout the day with temperature fluctuations.

The flow rate of other watercourses fed by rainfall depends on changes in precipitation.

Dam on the Rio Valgrande

Angela Boggero | Rights reservedMany watercourses are negatively affected by human water supply and even by small dams. An environmental impact assessment should therefore always be carried out before altering watercourse systems in any way.

Life in the water

Lago delle Rocce, Valle Orco

Antonello Provenzale | Rights reservedMountain water is inhabited by many and varied organisms. One of these is Daphnia pulicaria alpina. This small, dark-coloured, freshwater crustacean measures 3.5 millimetres in length and is found both in the Arctic tundra and in Alpine lakes.

Daphnia pulicaria alpina

Calling this crustacean small is paradoxical, because in the zooplankton community it counts as a veritable giant and a favourite food of fish.

How these organisms of the daphnia genus ended up Gran Paradiso National Park is a very long and complicated story, probably lost in the thousand-year cycles of glaciation.

A genetic study of its characteristics has revealed that populations in Alpine lakes are close relatives of their Arctic equivalents. They most likely survived in southern Europe at the end of the last glaciation, adapting to the Alpine environment.

The common frog also lives around Alpine lakes, having adapted to the mountain climate and the often extreme conditions found at high altitudes

Rana temporaria

The marble trout (Salmo trutta marmoratus) is another much larger inhabitant of many Alpine lakes and streams. Although native to the Gran Paradiso park, it is today increasingly rare and at risk of extinction.

One of its main threats was posed by the introduction of the brook trout, native to the eastern United States and Canada. There are many projects currently underway to remove the brook trout and give back living space to the marble trout populations.

Alpine watercourses are also populated by small species well adapted to the fast moving water,

including mayflies, insects that generally shelter under pebbles on the banks and beds of watercourses.

In some cases, natural selection has given these organisms a flattened body to help them withstand the fast-flowing currents, as well as claws to help them cling to substrates.

Mountain environments are home to many precious water bodies. Hidden groundwater emerges as springs, while large and small moving glaciers follow the rhythm of the days and seasons, eventually carving out valleys and creating lakes and streams.

These bodies of water constitute important ecosystems populated by many organisms that survive and transform, evolving over time and responding to their environmental conditions with endless adaptations of their form and life cycle.

The health of mountain aquatic ecosystems is currently under serious threat from the effects of climate change, pollution of human origin and uptake of water resources.

Even the smallest of actions, like reducing tap-water consumption, can play a crucial part in preserving a precious but threatened resource that is essential for life on the planet.